Welcome to the Women’s Caucus Featured Members page! It showcases our diverse members — from K-12 art educators to college professors — who demonstrate exemplary teaching, service, and research.

All featured members are asked to respond to the following questions:

• In what ways does feminism impact your practice?

• Who has been influential to you in your practice?

• How do you work towards empowering yourself, and others?

Current Featuring Member

Enid Zimmerman

Professor Emerita, Indiana University Bloomington

- In what ways does feminism influence your practice?

Feminism is wholly embedded in my research, teaching, and artmaking practice. For example, in the early 1990s, Frances Thurber (1946–2012) and I began to conduct research concerning empowerment and leadership themes based on feminist models for art education. Over the next decade, we were involved in researching issues in art teacher education and conducted a series of studies that focused on both theory and practice related to developing voice, collaboration, and social action as components of leadership in art education. Our goal was to instruct art educators to become empowered and take leadership roles in a variety of art education contexts focusing on the Artistically Talented Program at Indiana University and the Prairie Visions Program at the University of Nebraska. For over 10 years (1994-2004), we constructed several leadership and empowerment models for art education based on our research and practice by empowering art teachers to find their own personal voices, cultivating collaborative community voices with others, and going beyond their local communities and forming public voices. By 2002, we had constructed several pedagogical models as a result of our studies of various components of leadership and empowerment

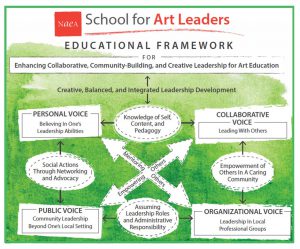

The Empowerment/Leadership Model for Art Education continued to evolve based on Thurber’s and my collaborative research and continued through my research from 2003 to 2012 that included doctoral and undergraduate art education students, international students, elementary education majors, and participants in the SummerVision DC program directed by Renee Sandell. In 2015, the National Art Education Association (NAEA) launched the School for Art Leaders (SAL) program to provide transformative experiences for art educators to become participatory leaders and advocates of positive change for the field of art education. Bob Sabol and I are both co-evaluators for the SAL program. Each summer 25 participants, chosen from a competitive application process, meet at the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas for five days to become part of a professional learning community empowered to assume leadership roles in a variety of educational settings. The Thurber/Zimmerman Empowerment Leadership Model was revised for SAL to meet contemporary needs for developing leadership in art education and another voice was added to emphasize developing feminist leadership in through participating in organizations at local levels.

(Figure 1). School for Art Leaders Educational Framework

Finally, I made a case for extending the leadership models to include creativity as a new component for considering leadership and art education. By rethinking about building feminist leadership models for art education, I believe my research and practice provides an avenue for new collaboration and community building based on the role of feminist empowerment and leadership in art education.

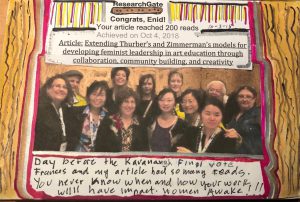

(Figure 2). Page from my daily diary entry dated October 5, 2018. Here I am surrounded by some of my doctoral students who have become feminist leaders in the US and around the world.

- Who has been influential to you in your practice?

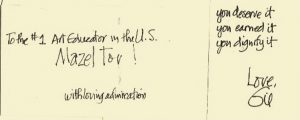

I was fortunate to be married to art educator and scholar Dr. Gilbert Clark, who was also my professional collaborator for 40 years. Gil was an original member of the Women’s Caucus a year before I joined. We wrote many articles, books, book chapters, and monographs together and traveled in the US and around the world doing over 40 workshops and presentations, while living and teaching in many national and international settings. Gil was always supportive of my endeavors and his support and our collaborations sustained me over many happy and challenging times. Gil passed away at the age of 90 in October 2018 and he is an inspiration to me in all that I do.

(Figure 3). Note to me from Gil after I received the 1998 NAEA National Art Educator of the Year Award.

I also was honored to receive the 1993 NAEA Women’s Caucus June King McFee Award. My 1979 dissertation, Explication and Extension of McFee’s Perception -Delineation Theory: An Exemplar for Art Education Theory Development, was based on June McFee’s work and she was most generous in responding to many queries I had about her theory. I also was most fortunate to have Mary Rouse as the mentor for my dissertation until her untimely death when Elizabeth Steiner became the Director of my dissertation. These three women played a significant role in my intellectual development and my dedication to feminist issues and concerns. In 1985, when I received the Mary J. Rouse Award from NAEA Women’s Caucus for an early or young professional and it had a deep and significant meaning to me. In the Art Education Department at Indiana University, when I was a student and then a faculty member, both Jessie Lovano-Kerr and Guy Hubbard were influential in my art education practice and scholarly pursuits. From 1980-1981, I served as President of the NAEA Women’s Caucus and many of my colleagues who were members were influential in my feminist teaching and practice.

When we were young art educators completing our dissertations, Mary Ann Stankiewicz and I met and immediately bonded over the lack of information about women art educators who had made significant contributions to the field of art education. In 1984, we wrote a chapter entitled “Women’s Achievements in Art Education” for the NAEA book Women, Art, and Education authored by Georgia Collins and Renee Sandell. Mary Ann and I then edited Women Art Educators (1982) and Women Art Educators II (1983), and in 1993, Kristin Congdon and I edited Women Art Educators III (all three volumes were funded by the Mary Rouse Memorial Endowment). In 1993, Elizabeth Sacca and I edited Women Art Educators IV: Her Stories, Our Stories, Future Stories and in 2003 Kit Grauer, Rita Irwin, and I edited Women Art Educators V: Conversations Across Time-remembering, revisioning, reconsidering both volumes were funded by the Canadian Society for Education through Art. In contemporary times, Debbie Smith-Shank and Karen Keifer-Boyd became editors of the on-line journal Visual Culture & Gender in which I have published and served as an editor.

I have had the privilege of learning from the many other art educators over the years. I believe in collaborating and cooperating with people from many different backgrounds and points of view. Below is a list of those art educators who have not been mentioned above. Their names are not in alphabetical order but in the order that I found articles and books we co-authored. I also would like to acknowledge Deborah Reeve, NAEA Executive Director, for all the professional encouragement and support she has offered me over many years.

Sharon LaPierre

Mary Stokrocki

Theresa Marché

Marilyn Zurmuehlen

Flavia Bastos

Marjorie Manifold

Melanie Davenport

Yichien Cooper

Melody Milbrandt

Kathy Milagria

Laura Zimmerman

Steve Willis

Mary Hafeli

- How do you work towards empowering yourself, and others?

A history of my own background, ways in which it has impacted my own professional and private life, and how I have worked to empower myself and others is documented in Through the Prism: Looking into the Spectrum of Writings of Enid Zimmerman edited by Robert Sabol and Marjorie Manifold (2008). As a participant as well as a program evaluator for SummerVision DC, over one four-day summer session in 2015, I learned to use data visualization methods, such as Renee Sandell’s Marking & Mapping® presented by Renee, to envision feminist leadership and at the same time map important concepts. In recent years, Renee Sandell and I have been collaborating by writing about and creating artworks on the topic of feminism and empowering ourselves and others. Based on our extensive past research and practice, in our chapter, “Feminist Leadership: Revelations through Data Visualization Mapping,” (in press) we discuss feminist leadership as revealed through two data visualization methods, Concept Mapping and Marking & Mapping®, that present ideas, perspectives, and directions for social change and empowerment through community engagement. Our goal is to help empower art education professionals seeking to expand their expressive potential as effective leaders. We base our methods on our many years, from the late 1970s to the present, of envisioning feminist leadership models for art education. Our emphasis is on equitable leadership as a transformative process that links theoretical foundations of feminist leadership to practical aspects of feminist artmaking and pedagogy. In our mapping revelations, Renee and I set forth an in-depth understanding about increased voice through participation, community building, and public voice that breaks down existing, yet outdated and unjust hierarchical notions and helps build transformational leadership experiences of empowered professionals where light and understanding can over shadow darkness and ignorance.

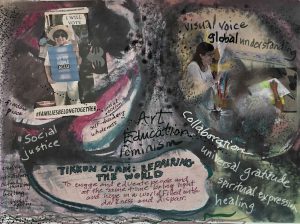

(Figure 4). Feminist Leadership: Not Feminist Leadership, in collaboration with Renee Sandell.

In a recent article Renee and I wrote, “Using Feminist Advocacy, Collaboration, and Arts-based Practices to Heal Ourselves and Others” (submitted to Visual Culture and Gender), we discuss how our transformative artmaking practices, viewed through a feminist lens, enable us to empower ourselves and others to help repair the world. Retired from university teaching, we both continue to be actively involved in art education advocacy and research at the local and national level and have returned to using our own art-based practices to nurture creativity, mindfulness, and critical thinking. We focus on empowering art educators to expand their expressive potential and thereby become advocates for art education research and practice. We do this by modeling our own and others’ art-making practices that link theoretical foundations of feminism with practical aspects of artmaking and pedagogy. The notion of Tikkun Olam: Repairing the World guides our art teaching and practices and is influenced by our common Jewish heritage. We focus on improving the world by performing small acts of social action as we create our own and collaborate artworks. In our artwork below, our community-building notions about developing an authentic voice is evidenced and emphasized through understanding that multiple points of view can be mollified towards overcoming darkness and despair by bringing light and hope to a troubled world through a contemporary feminist lens. We both exhibit our artwork, lead workshops, and use social media to advocate about how feminist theories can be put into practice.

(Figure 5). Tikkun Olam: Repairing the World in collaboration with Renee Sandell.

By mentoring and collaborating with future generations of feminist leaders, including those from a diversity of cultural, economic, and gender backgrounds, I believe positive changes can be made for all art educators in a variety of educational contexts that will impact those they teach and nurture.

References for the Three Questions

Sabol, F. R., & Manifold, M., C. (Eds.). (2008). Through the prism: Looking into the spectrum of writings of Enid Zimmerman. Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Sandell, R., & Zimmerman, E. (summitted in 2018 for consideration for publication to Visual Culture and Gender). Using feminist advocacy, collaboration, and arts- based practices to heal ourselves and others.

Sandell, R., and Zimmerman, E. (in press). Feminist leadership: revelations through data visualization mapping. In Keifer-Boyd, K., Hoeptner-Poling, Klein, S., Knight, W, & Perez de Miles, A. (in press), Lobby activism. Alexandria, VA: National Art Education Association.

Sandell, R., & Zimmerman, (2017). Evaluating a museum based professional learning community as a model for art education leadership. Studies in Art Education, 58(4), 292-309.

Stankiewicz, M.A., & Zimmerman, E. (1984). Women’s achievements in art education.

In G. Collins & R. Sandell, (Eds.), Women, art, and education (pp. 113-140). Reston, Virginia: National Art Education Association.

Thurber, F, & Zimmerman, E. (1996). Empower not in power: Gender and leadership roles in art teacher education. In G. Collins & R. Sandell (Eds.), Gender issues in art education: Content, context, and strategies (pp.144-153). Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Thurber, F, & Zimmerman, E. (1997). Voice to voice: Developing in-service teachers’ personal, collaborative, and public voices. Educational Horizons, 75(4), 180–86.

Thurber, F, & Zimmerman, E. (2002), An evolving feminist leadership model for art education. Studies in Art Education, 44(1), 5–27.

Zimmerman, E. (1997). Building leadership roles for teachers in art education. Journal of Art and Design Education, 6(3), 281–84.

Zimmerman, E. (1997). I don’t want to sit in the corner cutting out valentines: Leadership roles for teachers of talented art students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 21(1), 33–41.

Zimmerman, E. (1999), ‘“No girls aloud”: Empowering art teachers to become leaders. Australian Art Education, 22(2), 2–8.

Zimmerman, E. (2003), I don’t want to stand out there and let my underwear show: Leadership experiences of seven former women doctoral students. In K. Grauer, R. Irwin & E. Zimmerman (Eds.), Women Art Educators V: Conversations Across Time-Remembering, Revisioning, Reconsidering (pp. 107–121). Reston, VA/Quebec: National Art Education Association and Boucherville/Canadian Society for Education Through Art.

Zimmerman, E. (2005). Art education experiences of three Asian women formally doctoral students in the United States. Research in Arts Education, 10, 1–23.

Zimmerman, E. (2014). Extending Thurber’s and Zimmerman’s models for developing feminist leadership in art education through collaboration, community building, and creativity. In J. Daichendt, A. Kantawala & J. Haywood Rolling (Eds.), Visual Inquiry: Learning and Teaching Art, 3 (3), 363-278. Bristol, H UK: Intellect.

Past Featured Members

Christine Liao, Ph.D

Associate Professor, University of North Carolina Wilmington

• In what ways does feminism impact your practice?

Feminism showed me to question what was seen as the norm and reflect on the issues of equality. It also taught me to see the power relationship in my daily life and classroom. Being able to critically reflecting on these things changed the way I think and act. As an art educator, I try to bring the discussion of social justice issues to my class because I believe students need to be able to see and understand the issues and think critically so they can “see” the inequality in their daily life and beyond. This practice is influenced by feminism, and it allowed me to consider those issues relevant and important to include in my classes.

• Who has been influential to you in your practice?

Regarding my mentors and colleagues, my mentor Dr. Karen Keifer-Boyd definitely influenced me the most in my teaching and research. Her passion represented in many aspects in work and life is the goal I hold.

• How do you work towards empowering yourself, and others?

I am not sure “empowering myself” is a phrase I would use to describe what I do. I believe in feminist distributed leadership. To me, working with others and supporting others is “empowering” myself and others. Just listening is also my way to empower others. What is more important to me is the result of the empowerment. I think working towards changes realistically is empowerment. All in all, collaboration is my answer to this question.

Amy Brook Snider, Ph.D

(1940 – 2018)

Professor Emerita, Art and Design Education

Pratt Institute

A touching tribute by Jodi Kushins, PhD.

• In what ways does feminism impact your practice?

Both in my teaching and position as Director of Pratt’s Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC), I would use the structure of the consciousness-raising groups, spawned by the Women’s Liberation Movement during the 1970s, to facilitate discussions. About WAC’s Journal Project, I wrote:

The idea that teaching and learning are related activities and cannot be separated in a true educational community [consisting of students and faculty] was to be the central focus of The Journal Project…The meetings were lively. For each two-hour session, two or three journal writers were asked to pick an excerpt and make copies for all the members of the group. The excerpt was often about an [assigned problem] related to teaching or learning… A writer would read his or her excerpt aloud and… afterwards, the reader would first elaborate on the excerpt and the subject was open for discussion. No matter what the issue, it was clear that professors of [art, design]… or liberal arts were all fundamentally connected to each other through their teaching… Students would provide the teachers with the “other side” of a topic and vice versa; teachers from widely different disciplines gave each other fresh perspectives. It was a novel experience in the context of college teaching where few professors consult each other about what they do in the classroom and studio or discuss their teaching with their students (Snider and Williams, 2002, p. 4).

When I left Pratt Institute in 2014, my speech at my retirement party centered on another feminist value.

While I hadn’t yet read Nel Noddings in those early days, I was already applying what she called her “feminine approach to ethics and moral education.” Thus, caring relationships were at the core of our department’s values. As our spaces grew with each new location, the green velvet couch and table and chairs in the ADE computer lab, dedicated classroom with its circular arrangement of chairs, and the round table in my office, were places where such caring relationships were nurtured. My office came to resemble my childhood living room where the shared ideas, plans, failed projects, available jobs, teacher-student conflicts, and personal problems were either resolved or abled for further discussion (Leaving Home: Pratt Institute, Dec. 2014).

The following excerpts from my memoir in process exemplify my core values and reflect feminist principles.

-

It was in my office-cum-living room that I got to know my students and faculty through long and interesting conversations that often caused a bottleneck in the small outer office waiting area. For example, when I interviewed applicants for our two graduate programs, I always began the encounter with how did you get here and why now? The stories were fascinating and reminded me of Mary Catherine Bateson’s book, Composing a Life (1989) in which she describes how our lives are not the predictable linear progressions envisioned by children, planning what they wanted to be when they grew up. Increasingly, Bateson suggests, lives are improvisational as we respond to unplanned, random events with imagination and courage.

-

Repeatedly, I would hear a variety of reasons why these young, and not so young, applicants had first rejected the idea of becoming a teacher, although having a teaching parent was cited frequently. And yet many of them returned to their original dream of a life in teaching. Next, I would present them with the difficulties of that life to test their resolve. These conversations were often very personal and became the basis for some lasting relationships between several of the applicants who decided to enter the program, and me.

-

If we maintain a strictly “professional” stance toward our students, we make it difficult for them to relate to us as people. We are strangers in their world and they in ours and the classroom community remains an “us and them” situation. ‘Breaking out’ of the classroom and school walls as well as the traditional role of teacher and student whenever I could manage it, was an early strategy of mine.

-

I was increasingly involved in the art projects I designed for my students—not actually working with them but developing activities that were engaging to me. I was like the contemporary artists who make the plans for a fabricator or the conceptual artists who describe their works in texts on gallery walls without making them. The artist-teacher becomes a collaborator in the projects—either through designing the problem and its specific limitations or sometimes through a kind of marginal participation in the project itself.

-

I was using what I had learned from my experience in psychoanalysis and our consciousness raising group. In the process of analysis, lying on a couch with the analyst behind you and rarely commenting, I learned to listen to myself—I could almost visualize the words in front of me. And, in our group, I learned to listen closely to the other women, since one of the rules of consciousness raising is that there is no discussion until everyone takes her turn to comment on a topic. This kind of listening to oneself and another person closely is an important component of empathy, a quality that is essential in all human relationships. Then too, I learned that by being observed or listened to, one becomes more self-conscious and critical—a “reflective practitioner” (Schön, 1983). Producing that kind of teacher was one of the aims of our programs.

• Who has been influential to you in your practice?

The writers Herbert Kohl, Phillip Lopate, Jonathan Kozol, Eliot Wigginton, Robert Coles, Denise Levertov, and Vivian Paley; The late High School of Music and Art art teacher and friend, Sylvia Milgram; Art educators Brent and Marjorie Wilson, Terry Barrett, Ken Marantz, Marilyn Zurmuehlen, George Szekely, Harold Pearse, Cynthia Taylor, and Jodi Kushins, and several others.

• How do you work towards empowering yourself, and others?

As noted previously, during the gestation period of my development as a teacher of art in the NYC public schools and later, in my 36 years at Pratt Institute as an administrator and instructor, I’ve worked to empower the students and faculty both in the Art and Design Education Department and in the programs, I’ve developed or in which I’ve been involved.

Upon “retirement” in 2014, I chose not to retire but to reinvent myself using the broader lens of the art of teaching rather than art education. Thus, I have conducted professional development workshops for teachers in all disciplines and levels. And, for the past two years, the participants in Amy’s Salon for educators, who come from a variety of teaching and learning situations, have reinforced the efficacy of that perspective. This past year I initiated a group, Women in Retirement. During our first meeting where discussed issues related to retirement with a focus on the relationship between meaningful work and gender identity.

Finally, I am volunteering for the American Civil Liberties Union, an organization which I believe will empower individuals and organizations through its work in the courts. I am also planning to volunteer for Democratic New York State Senator Kirsten Gillibrand in her campaign for reelection, to ensure that women are better represented in the Congress.

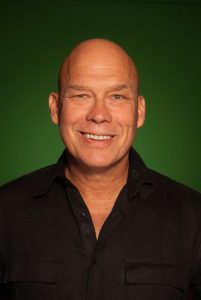

Jim Sanders, Associate Professor

Department of Arts Administration, Education and Policy

The Ohio State University – Columbus, Ohio

Photo by Dr. Bill Nieberding

Photo by Dr. Bill Nieberding

James H Sanders III, Ph. D. (Jim) is an associate professor in the Arts Administration, Education and Policy Program at The Ohio State University. Author and Founding Principal of the Arts-Based Elementary (NC Charter) School, Sanders came to academe after 26 years in non-profit arts administration. Sanders earned his Ph.D. in Education (Curriculum and Instruction) at the University of North Carolina Greensboro (1999), MFA at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale (1976), and BFA from Arkansas State University (1974). His research explores a tangle of topics including educational policy, material and visual culture, artful inquiry in the visual and performing arts, community cultural practices, and sexualities theories. Sanders was a founding trustee of the International Curriculum and Pedagogy Group, an engaged trustee of Ohio Citizens for the Arts, and has served as an InSEA Executive (Treasurer) since 2008.

Sanders writings have been published in peer-reviewed publications, including Qualitative Studies in Education (1999), Studies in Art Education (2006, 2008, 2013, 2014), the Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education (2009, 2013, 2014), The International Journal of LGBT Issues in Education (2005, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2012), Journal of Social Theory in Art Education (2003, 2005, 2010, 2013, 2014), Visual Arts Research (2006, 2007), the International Journal of Art and Design Education (UK with Kim Cosier, 2007), and International Journal of Education through Art (with Christine Ballengee-Morris, 2009), other journals and numerous book chapters. Sanders has delivered papers in North and South America, Europe, Asia, Australia and Africa in eleven national contexts.

In what ways does feminism impact your practice?

As an arts educator feminism is embodied by creating dialogical learning spaces where open exchange nurtures collaborative, ongoing inquiries; By arranging classroom seating in circular form, students are reminded they can reshape the environments that discipline their dialogues. Dissembling hierarchies and an honoring of our collective voices our rehearsals of caring exchange take form.

The above addresses an embrace of equitable exchange of personal testimonies and distributions of leadership roles that encourage all class participants’ engagement – at times this includes sharing edibles as a signifier of nurturance. Soliciting not only student insights and their shared personal testimonies, I aim to attend to their physical health and comfort with pleasure—acknowledging forms of communication and creativity too frequently ignored in academe. In nurturing shared consciousness raising practices first wave feminist performed pedagogical, political and personal form of self-empowerment are experienced as we collectively develop new ways of embracing exchanges of caring, nurturance and honoring those foremothers who have birthed our practices. In honoring those women who shaped my pedagogical practices and world views (many listed below) my simple psalms sing their praises and reaffirm a love for the lessons they’ve so generously shared.

- Who has been influential to you in your practice?

I was also blessed to be surrounded by gay and lesbian role models, and especially the working class lesbian community in our All-American City (Woodstock, Illinois) that taught me to work with horses, ride a motorcycle, and live openly when one could do so safely, and when that was impossible, valuing the larger community of women and gay men who introduced me to new worlds in which we could collectively thrive and learn.

aesthetic direction that engaged and worked through the body.

testimony and appreciation for consciousness raising (reading and subsequently interacting with George Noblitt, Madeleine Grumet and Bill Pinar).

- How do you work towards empowering yourself and others?

Working with/in communities of strong women at The Ohio State University, especially those in the Department of Arts Administration, Education and Policy (especially Christine Ballengee-Morris, Vesta Daniel, Margaret Wyszomirski, Debbie Smith-Shank, Karen Hutzel and Candace Stout) and feminist-friendly male colleagues Mike Parsons and Terry Barrett, I gratefully accept their guidance, mentorship, and support. Working with an even larger community of colleagues (Kim Cosier and Pat Stuhr in Wisconsin, Elizabeth Garber in Arizona, Laurel Lampela in New Mexico, Jill Vexler, in New York, Nick Cave in Chicago, and Karen Keifer Boyd in Pennsylvania) all having generously read and responded to works in progress, and challenged my clearer articulating of positions. Christine, Debbie and Karen have co-authored articles with me, and shared their approaches to administrative leadership, teaching and mentorship. I daily attempt to embody many of the practices each of these colleagues so exquisitely embody on a daily basis, and in their footsteps I hope to move through my work in this field.

community arts leadership wisely practiced by Paula Berg Owen (Southwest School of Art and Craft, San Antonio, TX), and founder of Women and their Work (Austin, TX), Pat Land. I have been empowered by many of the women and men Pat looked up to, including Liz Lehrman, Linda Burnham, and dancers Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane (respectively reminding me that the personal is political, and haunting my mindfulness that our practices in repeatedly-becoming, must be engaged and entangled in everyday practices that remind us of those sacred fields in which we labor (here also referencing my dearly beloved Celeste Snowber, and sister Canadians Rita Irwin and Kit Grauer).

Jim with Grandkids James (V) Tyler, Kristine Ariel and Sarah Jayne at Hoover Dam July 3, 2015

Caryl Rae Church, M.A.

K-5 art educator in Perry Schools, Lake County, OH

• In what ways does feminism impact your practice?

Feminism has taught me the value of questioning power relationships and equity in my classroom. Feminism has also led me to collaborate with a range of people who have given me opportunities to grow and challenged my thinking. I have embodied that in my teaching and pass it on to my students. The meaning and purpose of teaching is to empower and liberate my students so that they can unfold into themselves without the restrictive conditions of society. Feminism has provided the basis of research and knowledge that supports that work. When students know they are valued by others and feel valuable inside themselves, they blossom. This is what teaches empathy, appreciation and understanding of each other’s differences. Feminism is the lens through which I view the world and the negotiated space where theory and praxis overlap.

• Who has been influential to you in your practice?

I have been blessed to know, study, and collaborate with many wonderful educators, feminists, and artists. Each has given me a piece of inspiration for living and practicing art education. Most influential in my practice would be my students. They teach me so much about fairness and challenge my comfort zones. Their perseverance inspires me to keep working for equity. My professors Dr. Linda Hoeptner-Poling, Dr. Scott Sherer, and Dr. Anninna Souminen, educators and friends Debbi Mayo and Anne Ondrey and wise women Helen Baith and Erin Gannon have been very influential in the development and continuous refinement of my practice.

• How do you work towards empowering yourself, and others?

Empowerment happens when people feel able to choose. Therefore, I take a lot of care in creating a space where choice is honored. Decision-making involves discernment. Discernment implies wisdom behind a judgment. In regards to both mine and my students’ empowerment, I think that a mixture of wisdom, knowledge, curiosity, courage, and freedom is necessary. I make my students feel safe, knowledgeable and capable to follow their curiosity enabling them make decisions based on their truth. I strive to inspire them to create that for others. I also spend a lot of time teaching kids how to listen. Not just to listen for instructions, but the deeper listening that leads to awareness of what is happening inside themselves and in nature. Waking up to your own wisdom, accessing the wisdom of your surroundings is the doorway to empowerment. What my students and I create with that wisdom is valuable, even if that is not the majority’s opinion. Additionally, how students share the responsibility of caring for one another’s right and freedom of choice is a lesson that can transcend art. Holding space is simply part of the experience of being an artist. That is the space of empowerment.